Saturday, March 25, 2023

10:00 a.m. – 2:00 p.m.

Women began working in railroad jobs initially as telegraphers in the late 1830s and early 1840s while telegraph lines expanded alongside new railroad tracks. During the Civil War (1861-1865), as men were drafted into the military, more than 100,000 women were recruited as telegraphers, ticket agents, and station agents, managing railroad operations and train crews. Jobs for women in the railroad industry fluctuated, depending on the need for men in the military, and jobs were again plentiful during World War I (1914-1918). In addition to station agents, women began working in mechanical shops, roundhouses, and railroad right-of-ways. During the Depression (1930s), women were again expected to give up their jobs for men, but a few stayed on as telegraphers and station agents. During World War II (1941-1945) railroad jobs for women were plentiful again but decreased after the war.

As civil rights and equality changed employment opportunities in the 1970s, college-educated women entered the workforce in greater numbers leading to dramatic changes. Women moved into “operational” jobs previously only held by men, including switchmen, yardmasters, and brakemen. They also became electricians, dispatchers and locomotive engineers. This represented a significant change for women working on the railroad – from more clerical, communication jobs to operational work – as women continued to work in all aspects of the railroad.

Christine Gonzalez

Ramona Dockter

The mid-1970s saw the first women pioneer careers as locomotive engineers. Bonnie Leake (in this page header) worked for the Union Pacific (UP) for nearly 40 years, first as a clerk, then a fireman for 8 years, and in 1974 became the first woman trained at UP as a locomotive engineer. Christine Gonzalez became the first Class 1 engineer on the Santa Fe railroad in 1974, after initially training as a hostler that moves engines around the yards. Ramona Dockter became the first freight train engineer in the USA in 1976 for the Burlington Northern RR after working for 6 months as a brakeman. Edwina Justice (top color photo) became the first Black woman locomotive engineer for Union Pacific in 1976 and hauled livestock and freight from North Platt, Nebraska to Cheyenne and Denver for 22 years.

Sarah Clarke Kidder

Railroad Leadership Roles

Kathryn Farmer

Sarah Clarke Kidder was the first woman president of a railroad in the world and successfully ran the Nevada County Narrow Gauge Railroad from 1901-1913. There are numerous women in a variety of administrative leadership positions in railroading today. Kathryn Farmer was appointed the first President and CEO of a Class 1 Railroad by BNSF in 2021.

Women’s Contributions to Railroad Inventions

In addition to working on the railroad, women were responsible for major improvements to railroad safety and travel.

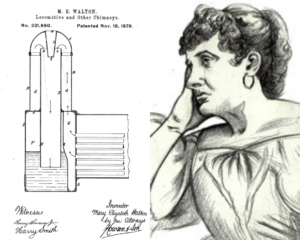

Mary Walton

Mary Walton was an environmental engineer who in1879 developed a way to deflect factory smokestack emissions using water tanks where the pollutants were retained and later flushed out more safely to redirect smoke and other pollutants out of the air. This system was later adapted for steam engines notorious for releasing large amounts of soot, smoke and air pollutants. Mary Walton also invented a cotton and sand dampening system for reducing the noise produced by elevated railway systems. Her noise deadening invention patent of 1881 was sold to the Metropolitan Railroad and adopted by other elevated rail companies. A more well-known inventor, Thomas Edison, had previously tried to solve the noise problem but failed. Walton also traveled to England to promote her inventions which were adopted and hailed internationally.

Eliza Murphy was an inventor who created a packing device to lubricate train axles with oil to prevent wheel bearings from seizing which significantly reduced train derailments. She held 16 patents for her packing devices that improved railroad safety.

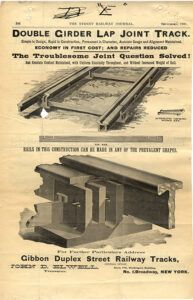

Catherine Gibbon track

Catherine Gibbon revolutionized the way train tracks were constructed in 1890. Where previously track required 28 pieces of metal, her Gibbon Double Girder lap-Joint Track was constructed with about 6 parts and was more stable, smoother, and easier to install and maintain. She held several patents related to this invention.

Mary Riggin filed a patent in 1890 for the first Railway Crossing Gate that warned pedestrians and drivers of approaching trains. Prior to her invention accidents with trains, wagons, and pedestrians were quite common. This crossing gate was a precursor to today’s automated gates.

Mary Riggin filed a patent in 1890 for the first Railway Crossing Gate that warned pedestrians and drivers of approaching trains. Prior to her invention accidents with trains, wagons, and pedestrians were quite common. This crossing gate was a precursor to today’s automated gates.

Olive Dennis was a civil engineer originally hired by the B&O railroad to design bridges. The President of B&O decided that since half of rail passengers were women the task of engineering upgrades to rail travel might be better designed by a woman engineer.

Olive Dennis

Olive Dennis became the first “service engineer” in America. She revolutionized passenger train travel by introducing reclining seats that could partially recline; stain-resistant upholstery, larger dressing rooms for women, individual window vents (which she patented) to allow passengers to bring in fresh air; and, later, air conditioned compartments. Other rail carriers followed suit in the years that followed, and buses and airlines, in turn, had to upgrade their level of comfort in order to compete with the railroads. In 1947, B&O Dennis with designed an entire train that incorporated all of her innovations, called the Cincinnatian, which operated until 1971. Despite having designed the train she received little recognition or publicity for her work since her design patents had been signed over to the railroad.